Before leaving Rockhampton, Karl sat for a portrait at the Doré photography studio*, operated by P.M. Walker on East Street. It remains my favourite image of him—stoic and steady, yet with a quiet warmth in his expression. There’s something undeniably wholesome about this photo.

After that final moment in the studio, Karl departed Rockhampton on June 15 and arrived in Mackay three days later. His journal entry for the journey is, as always, understated:

“I strayed into the bush at different times but managed to get onto the track again, in each case, and was followed by Dingos once or twice, but they are not at all dangerous except in packs.”

The terrain between towns, some 60 to 80 miles apart, was rough, but perhaps even rougher was what Karl wasn’t fully disclosing: he was travelling while recovering from Dengue fever. The mosquito-borne illness had been misdiagnosed as something far more dire, bubonic plague. Given the outbreaks then affecting Sydney and Brisbane, Karl had initially been placed in quarantine before the true diagnosis emerged. Thankfully, he was among the lucky ones who experienced only the milder, flu-like symptoms.

Despite this, he pressed on, and Mackay gave him a hero’s welcome. The local paper announced a "smoke concert”** in his honour, praising Karl’s "pluck and perseverance." Plans shifted, however, when women in the community expressed a desire to attend. What was originally meant as a male-only gathering evolved into a full-fledged social evening, headlined by Karl’s second lecture on his travels.

Programme – Benefit Concert for Mr. Karl M. Creelman

Britannia Hall, Tuesday, June 26, 1900

Overture – Bijou Orchestra

Songs by: Mr. W.H. Brookes, Miss Dimmock, Mr. Mackie, Miss McKenney, Mr. F. Weir, Mrs. Holly, Mr. T. Armour, Miss Houston, Mr. R. Moyle, Miss McLellan, Mr. A. Rigby, Miss T. McLellan, Mr. R.M. Sneyd

Final Selection – Bijou Orchestra

The concert was well-attended and spirited. The local newspaper reported that Karl’s talk about his 14-month journey from Nova Scotia captured the crowd’s full attention and was met with generous applause. A dance closed out the evening, and the next day Karl resumed his ride north, setting his sights on Townsville via Bowen.

While the townspeople were intrigued by Karl’s tales of North America, he, too, was absorbing Queensland’s character with genuine curiosity. In a letter home, he wrote:

“It is true the country is very sparsely settled, the towns very small, few and far between, and in the bush the stations (or ranches, as they are called in Canada), are often over a hundred miles apart, but the whole of Queensland can be travelled over without any danger of starving, or dying of thirst except in the northern territory.”

He also noted how deeply local economies were tied to the land:

“This town (Mackay) with its 10,000 inhabitants depends entirely on the sugar crop. If it is a failure, then there are bad times in the town, but if the crop is good, business is correspondingly good.”

Karl’s commentary on sugar was just the beginning. What he witnessed was the legacy of an industry that had taken root decades earlier. Sugarcane first arrived in Australia in 1788, but it wasn’t until the 1860s that it gained commercial significance.

The expansion of sugar plantations brought with it a darker chapter; over 60,000 labourers from Melanesia and surrounding islands were brought to Queensland between 1863 and 1904. While some arrived voluntarily, many were victims of kidnapping or coercion, a practice known as blackbirding. Government reforms would later halt this system, but it left behind a definite stain on the industry.

Following this, waves of Italian and European migrants took up the work, many of whom eventually became landowners and small-scale growers. Today, many of Queensland’s sugar farms remain family-run. What I learned is that the industry also boasts one of the most intricate rail systems in the world, approximately 4,000 km of narrow-gauge track weaving through the coastal towns. These “tramways” operate around the clock during the 20-week crushing season, transporting freshly cut cane to nearby mills within hours of harvest. It takes about eight tonnes of cane to produce one tonne of raw sugar, and the entire process is synchronized to prevent spoilage and ensure peak efficiency.

So while in MacKay, Karl may have been admired for his endurance and adventurous spirit, but he was also a keen observer of place and people. As he moved northward, it was clear that Australia, too, was leaving an impression on him.

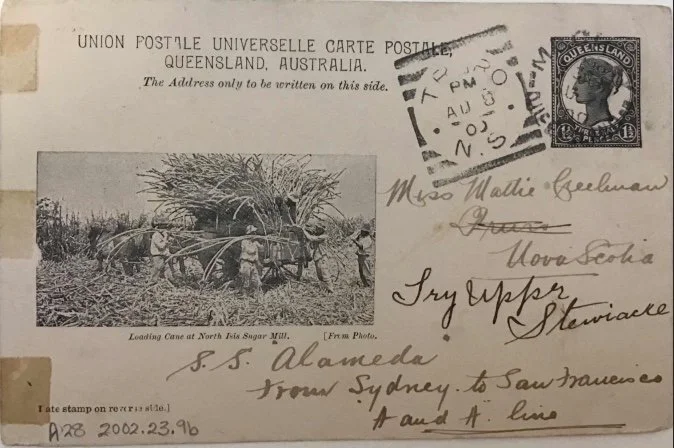

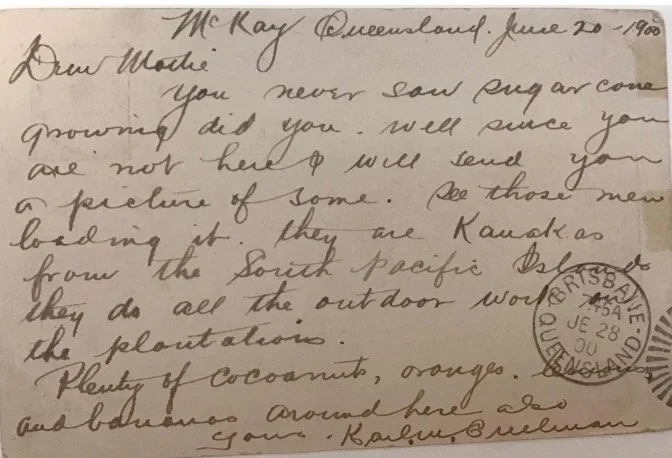

It was from MacKay that Karl sent a postcard to his younger sister Mattie dated June 20, 1900: Dear Mattie, You never saw sugar cane growing, did you? Well, since you are not here, I will send you a picture of some. See those men loading it, they are Kanakas from the South Pacific Islands they do all the outdoor work on the plantations. Plenty of coconuts, oranges, lemons and bananas around here also. Yours, Karl M. Creelman.

*Walker’s Doré Studio operated at 129 East Street, Rockhampton, from 1892 to at least 1900.

**A “smoke concert” was traditionally an all-male social evening featuring food, drink, smoking, and entertainment—often with speeches or performances. The event in Mackay, however, broke tradition to include women, transforming the evening into something more inclusive.

If you are new to the Karl Chronicles, get caught up on our expedition around the world!

Start here: 200 highlights from 200Chronicles

Then get caught up on the rest of our journey, click here for more Karl Chronicles

Click here to check out my art store

The Karl Journey is now registered as an official expedition with the Royal Geographical Society