In 1919, Thomas Edwards took out a permit on 2421 Granville Street, Vancouver, for a ‘4-storey brick building’ for apartments, an undertaking business, and a public hall and lodge room for the “Odd Fellows”. The Odd Fellows were evicted the following year as a result of having noisy parties. There was a proceeding court case to cancel the lease to the lodge, citing: “because the mirth and sounds of dancing from the Odd Fellows’ Hall above his undertaking parlors at 2421 Granville street, disturbed the solemn ceremonies in his Undertaking Parlors.” The lodge then acquired land nearby in Fairview and opened their own building in 1922, presumably where Karl worked until his death.

The funeral home and undertaking business at 2421 Granville Street closed in 1933, but the building still stands today, now home to retail spaces and apartments.

Karl was then buried at the Ocean View Burial Park about 15km from South Granville in Burnaby, B.C. The Ocean View Cemetery Company purchased the 40-acre site at 4000 Imperial St. in 1918, opening interments shortly thereafter.

Ocean View Burial Park was British Columbia’s first non-sectarian, for-profit cemetery. Created by a group of local investors, it offered a resting place not tied to a church, civic body, or fraternal order. Every plot included perpetual care, a defining feature at the time. In the wake of the First World War, many of the earliest sections were given patriotic names like “Empire,” “Dominion,” and “Crown.”

Its landscape design was the work of Albert F. Arnold, who believed cemeteries should be beautiful, peaceful places rather than “long-grassed spaces of unhappy memories.” A local newspaper described the grounds as having “ornamental trees and shrubs, beautiful flower beds, smooth winding walks and drives, with a total absence of the usual ostentatious reminders of the harvest garnered by the grim reaper.” Instead, modest markers, neat lawns, and carefully-tended flowers were meant to honour those laid to rest more gently.

Today, there are more than 100,000 people laid to rest at the cemetery, including Karl.

It is a lovely place. I’ve always been drawn to cemeteries while travelling, especially in foreign countries, because they reveal how cultures remember their dead. They’re contemplative spaces, often peaceful, often beautiful, and they say as much about the living as they do about those who’ve passed.

I had arranged to meet with staff member David Clarke for help locating Karl’s exact resting place. I knew the section, lot, and plot number, but Ocean View is vast, and it takes a practiced eye to navigate it. David walked me through the grounds until we reached the northeast corner, to the section, ironically and appropriately for Karl, which is named “Empire”, Lot 80, Plot 3.

No headstone or footstone marks Karl’s grave. Using the original plot maps and his knowledge of the cemetery, David pinpointed the exact spot.

It was a beautiful day, June 12, 2024, when I was there, and standing at the place Karl was buried felt unexpectedly emotional. For nearly a decade, Karl has been my companion, my guide, my obsession… my ghost. Finding the place where he actually rests made him feel suddenly, quietly, real. After David left, I lingered. I noticed the space sits near a tall conifer — a cedar, I think — which lends Karl’s plot a sense of dignity. The view is lovely, set apart from the busier pathways and roads. The section has remarkably few stones, but there is one marker nearby: Arthur J. Brownell and Minerva M. Brownell. Minerva was Karl’s sister, the third daughter born to the Creelmans. Minerva was two years older than her younger sister, Mattie.

At first, I was upset that Karl had no stone of his own. I wanted the world to know a remarkable man lies here. I wanted something to point to, something to touch. But in time, I realized that it was about my need for recognition, not his. There is humility in his unmarked plot, a quietness that suits Karl.

And perhaps it was intentional because Karl does have a stone, just not where he is buried.

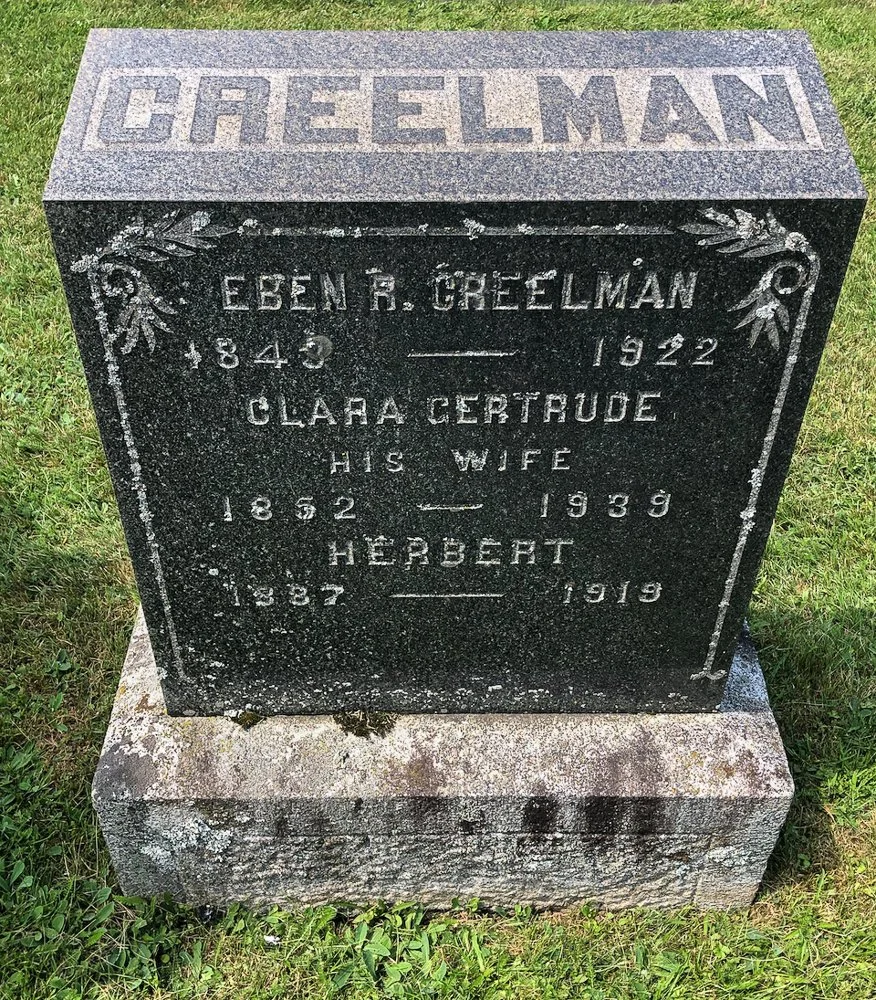

His father, Ebenezer Ross “Eben” Creelman, died in 1922, two years before Karl, and is buried in the Truro cemetery in Nova Scotia. His large granite stone bears the name “Creelman” in bold capitals. Engraved on the front are Eben’s dates, those of his wife Clara Gertrude (who lived to 87), and of their youngest son, Herbert, who died in 1919 at the age of 31.

On the side of that stone, two more names are carved:

Karl M.

1878–1924

Jean S.

1876–1938

Karl’s name is permanently etched in his hometown, beside his sister.

So while Karl’s body rests near a tall tree in Burnaby, surrounded by quiet lawns and near the sister who shared his corner of the Empire section. The name that marks his life, the name people can visit, touch, and remember, is at home in Nova Scotia, with his parents, brother, and sister.

If you've enjoyed the Karl Chronicles, please share this post with others

It's a labour of love, and every share helps keep this piece of Canadian history alive

The Karl Journey is registered as an official expedition with the Royal Geographical Society