Dear reader, while writing these last few posts, I, too, have found myself on the lecture circuit. I was thrilled to have an audience at the Colchester Historeum and, more recently, at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.

I hope my audience was satisfied — and that my “lecture was well worth hearing; instructive, entertaining, and at times amusing, all told in a straightforward manner without blow or ostentation of any kind,” as the Westville Standard once wrote of Karl’s own lecture.

For me, there were no reviews in the local papers, no mention of my “plucky oration skills,” but some very kind comments on social media and wonderful questions from the audience gave me reason to believe they were engaged.

However, sadly for my audience, what’s been missing is the prelude to the lecture —the kind of lively, warm-up Karl’s crowds enjoyed. For that, I must refer you back to Karl’s stage companions in Australia, who offered a program that looked something like this:

🎵 The Old Brigade – Mr. H. Portus

🎭 Comic Song: I Happened to Be There – Mr. A. Cerr

💪 Club Swinging Exhibition – Mr. R.G. Carter

🎵 The Little Hero – Mr. W. Hearn

🎵 Mary of Argyle – Mr. J. Murphy

Dear reader, I have yet to attempt a comic song or solicit volunteers for a club-swinging demonstration, though perhaps I should?

Instead, I’ve endeavoured to structure my lectures as thematic stories rather than chronologically, emphasizing the narrative through images uploaded to PowerPoint and projected onto a large screen.

Effective, yes, but hardly magical.

In contrast, Karl’s lectures included something close to magic: the magic lantern. You’ll recall from the review of the Parish Hall lecture in Pictou that Karl’s presentation included “fine lantern views,” one of which showed him proudly mounted on his Red Bird bicycle.

So, what exactly was the magic lantern?

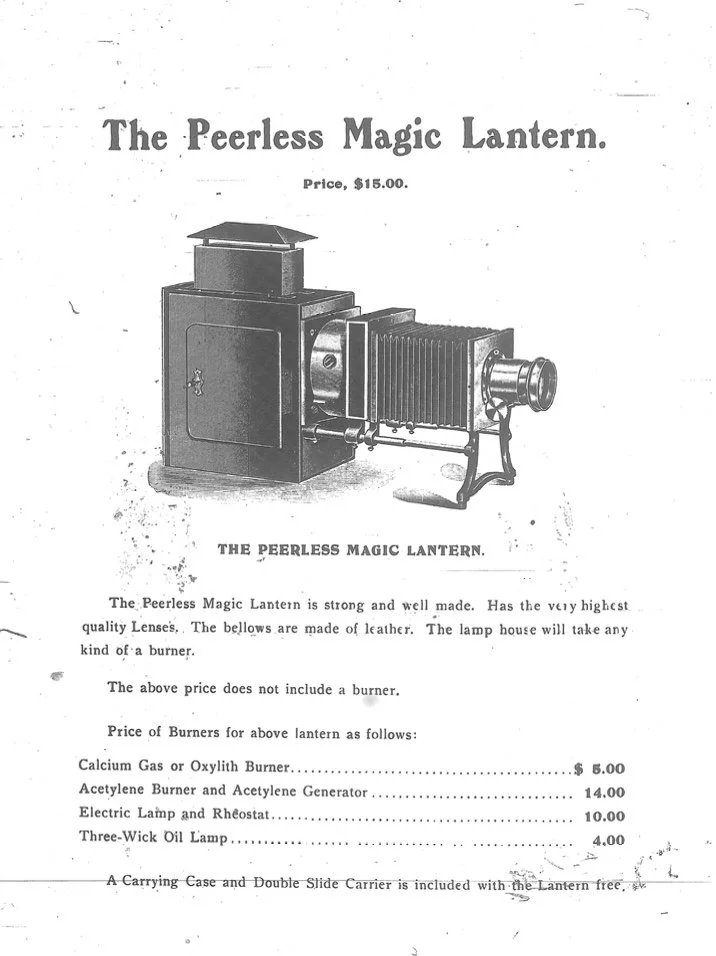

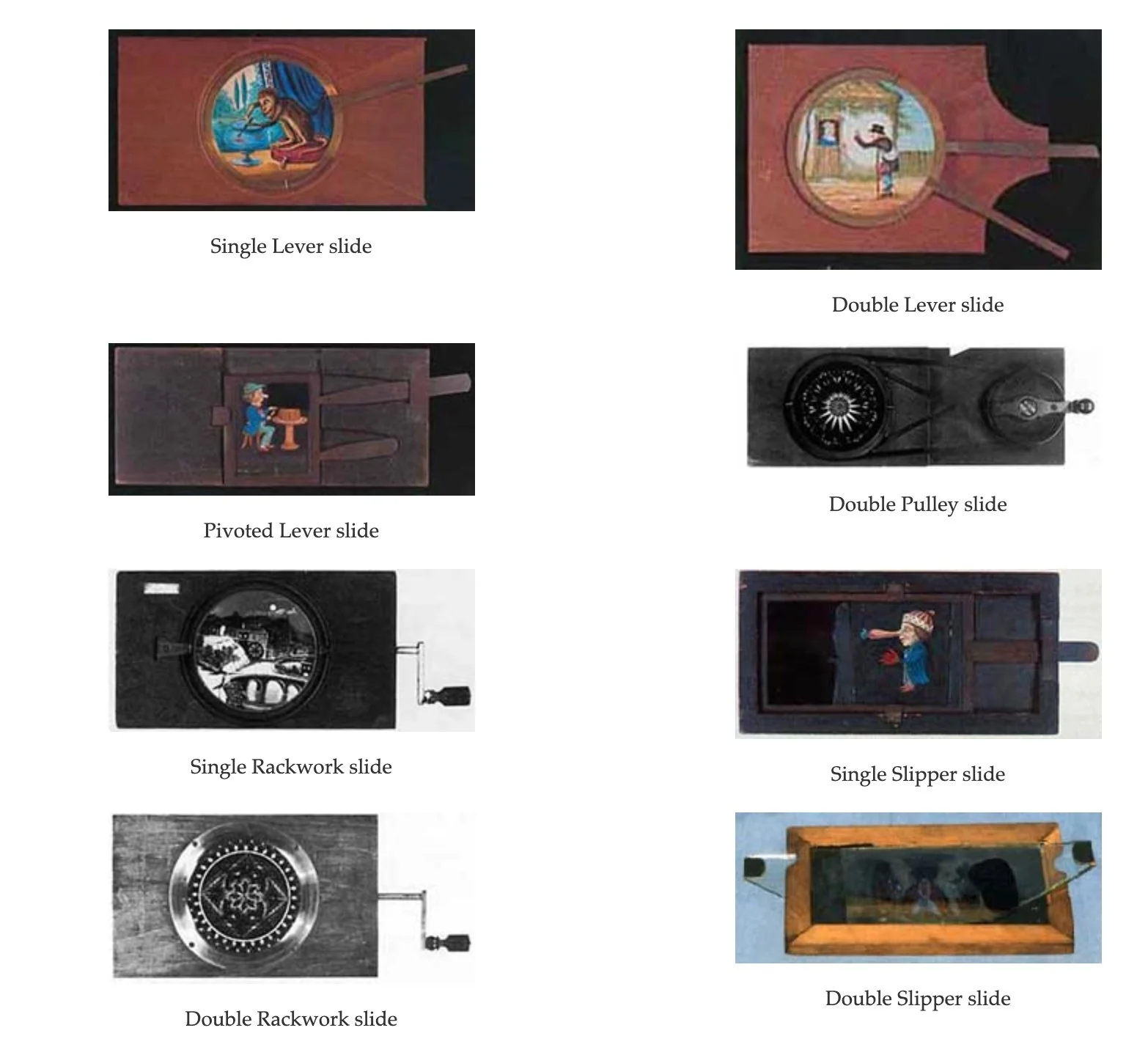

The magic lantern, first developed in the 1600s by a Dutch scientist, was the earliest form of slide projector. Imagine a bright light, first a candle, then oil, limelight, kerosene, and ultimately electricity, shining through a painted or photographic glass slide before being magnified through a lens onto a wall. To early audiences, devils, angels, and ghostly figures seemed to appear out of thin air, hence the name “magic.”

By the 18th century, lanterns were widely used across Europe for both education and entertainment. In America, the first recorded “lantern show” took place in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1743, promising “entertainment for the curious.” By the mid-19th century, improved light sources allowed shows to be staged for thousands, sometimes referred to as phantasmagoria, where moving slides created dancing skeletons, drifting ghosts, or fiery devils, often projected onto smoke to heighten the illusion.

When Karl’s lanternist dimmed the lights and slipped in a slide of him on the Red Bird, I imagine his audience was instantly transported. To see the world appear on a wall, flickering and larger than life, at a time when most people had only ever seen small photographs, that was truly magic.

By Karl’s time, the magic lantern was everywhere: in churches, schools, and local halls. The technology had become increasingly sophisticated, with dual or triple-lens lanterns for dissolving views and seamless transitions, an early form of the slideshow.

By the 1950s, the projected image evolved again with the arrival of the 35mm slide and projectors like the Kodak Carousel.

But the magic never fully disappeared. The traditional lantern has enjoyed something of a rebirth. There are now several Magic Lantern Societies hosting annual conferences, buy-and-sell exchanges, and live performances. Some participants step back in time, performing as historical “lanternists,” while others use antique slides to create new art, blending 19th-century craft with modern interpretation.

If you’re curious, check your local Kijiji or eBay listings: lanterns and slides still appear at auctions, antique shops, and flea markets. The light sources have been modernized for safety, but the brass fittings and hand-painted slides retain their old-world charm.

Many living history museums also hold them in their collections. At the Beamish Open Air Museum in Northumberland, England, a magic lantern sits proudly in the church. Closer to home, the staff at Citadel Hill in Halifax offer a seasonal Magic Lantern show each Christmas, dimming the lights to project vintage slides to their modern audiences. I spent time with the staff there, learning about their lanterns and poring over their slide collection.

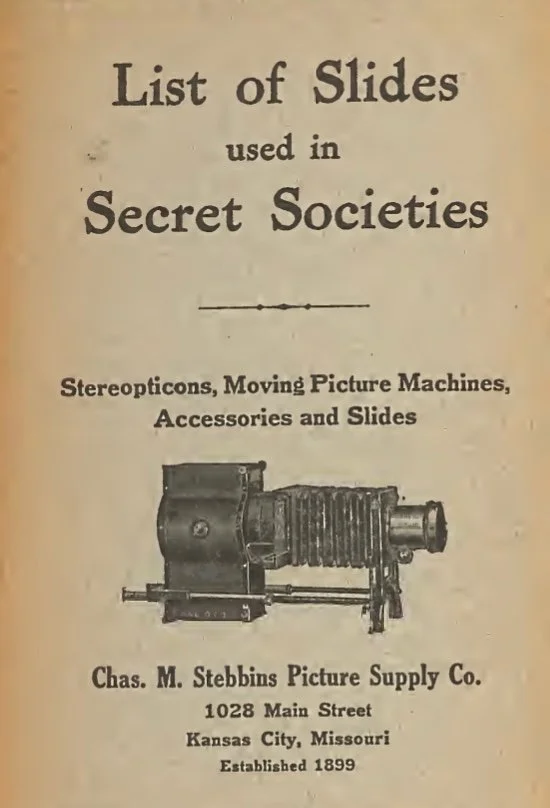

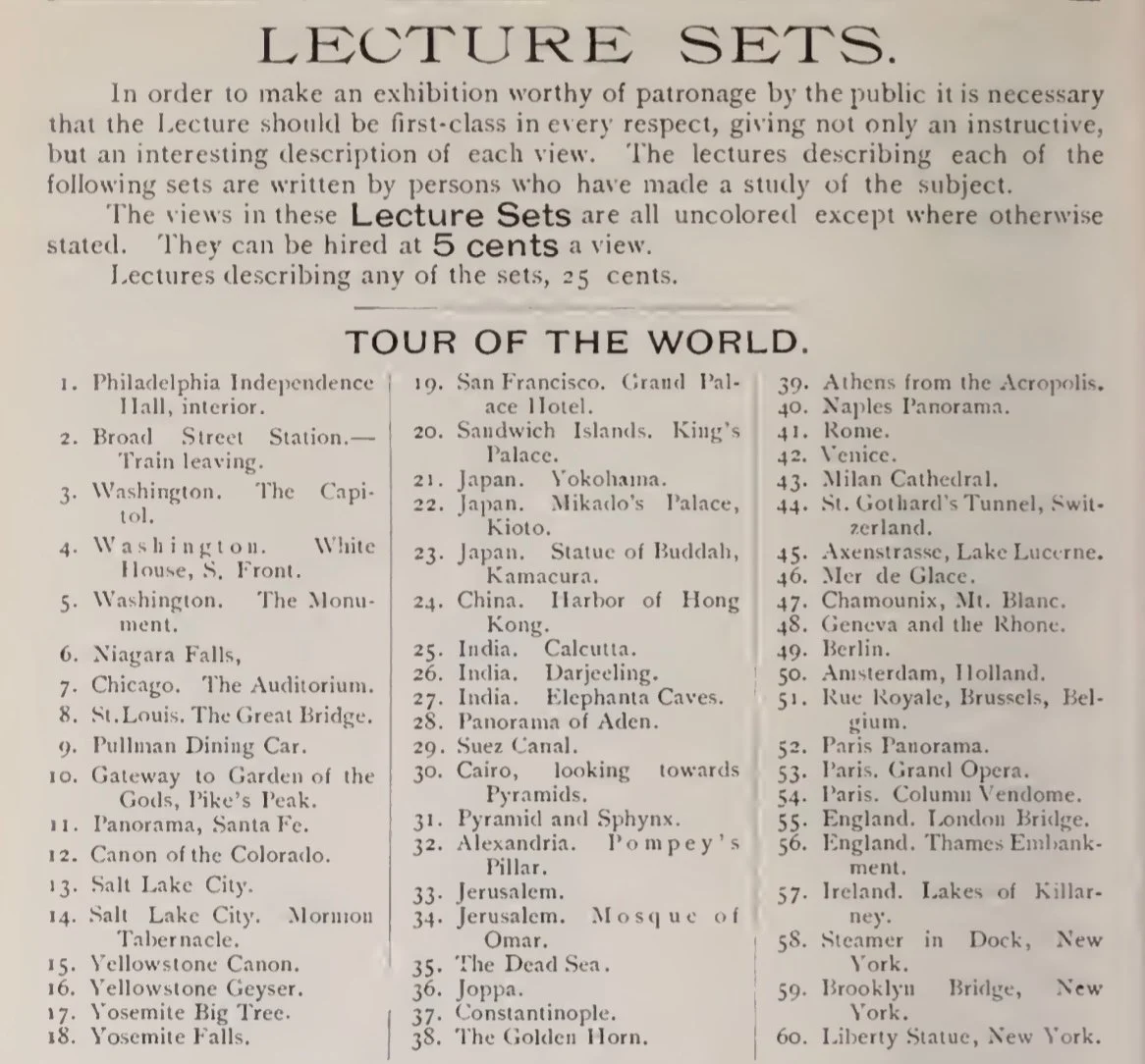

I’ve since joined the Magic Lantern Society, and I’ve done my share of research. I suspect Karl may have used some of his own photographs as slides, perhaps even that image of him on the Red Bird. But given the limited number of photographs from his journey, it’s possible the lecture venues purchased a set of world travel slides. Lantern catalogues offered collections of scenes from around the globe, often accompanied by booklets of narration — essentially the earliest form of a film script.

Today, I click a remote and advance to the next slide in PowerPoint. Practical, yes. Magical? Not quite.

But as I stood at my lectern this month, sharing Karl’s story with my own images glowing on the screen, I felt a faint kinship with those 19th-century halls — a darkened room, a flicker of light, and an audience leaning forward to see the world through my lens.

As for my prelude show, my loyal reader and new friend Trevor once said that my song might well be “I Was Born Under a Wand’rin’ Star.” I’ll take that.

Now, about that club swinging…

If you've enjoyed following Karl's journey, please share this post with others.

It's a labour of love, and every share helps keep this piece of Canadian history alive.

Then get caught up on the rest of our journey, click here for more Karl Chronicles

The Karl Journey is registered as an official expedition with the Royal Geographical Society